The History of John Rutsey and Rush

Rush survived more than 40 years in the music industry, persisting through critical hatred and shifting musical trends. They owed much of that longevity to the consistently inventive drumming of Neil Peart. Within that view, it's easy to miss the band's important first chapter with John Rutsey, their founding drummer.

While Rutsey may be remembered as Rush's version of Pete Best, his story is worth revisiting.

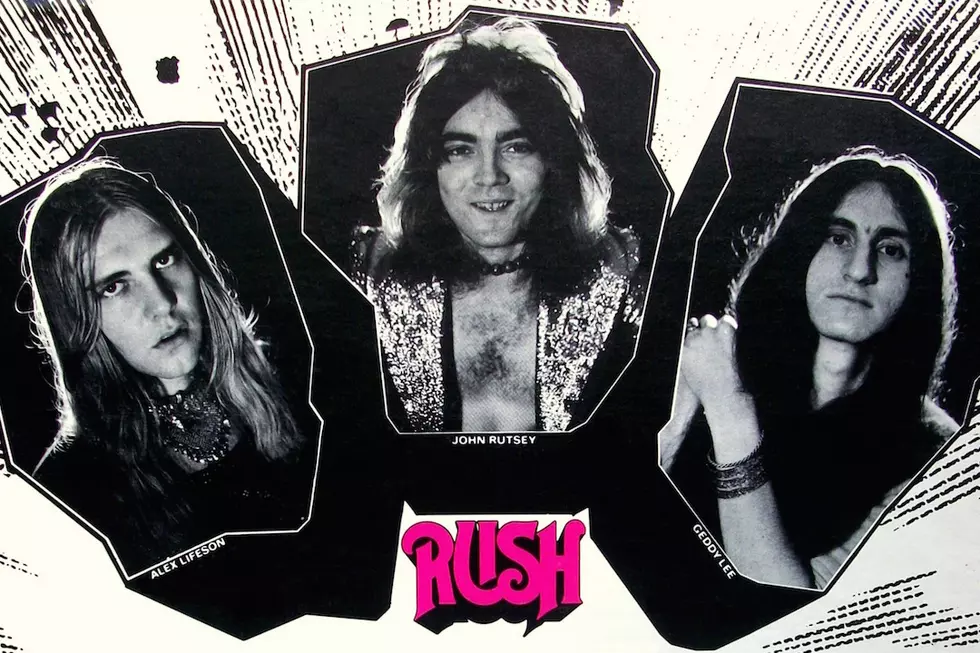

The first seeds of Rush were sewn in 1963. Hockey buddies Rutsey and Alex Lifeson met while attending the St. Paschal's School and eventually formed a band dubbed the Projection. Then in 1968, in the Willowdale area of Toronto, the teenagers joined forces with bassist Jeff Jones, who was soon replaced by Geddy Lee, a somewhat witchy-looking dude with a high-pitched shriek of a voice and an enviable fluency on his instrument.

In his 1988 biography Rush Visions, author Bill Banasiewicz discussed Rutsey's importance as a motivator: "John was the guy who would bug everyone to practice, and I think thought of himself as a 'rock and roller.' I've said it before and I'll say it again: There would have been no 'Rush' without John. ... Anyway, John led the guys as far as being 'glam rockers,' with really flashy jackets and pants, and eight-inch high boots. One time, he was speaking to me at the Gasworks and I said, 'Didn’t we used to be the same height (5’8”)?' He laughed and said, 'Well, maybe a long time ago!'"

Later, Banasiewicz tells the Rush band name origin story, explaining that it was Rutsey's brother Bill who christened the trio.

"The band was excited, but they had a big problem," Banasiewicz writes. "While they had been dreaming of playing, they had neglected to come up with a name for their group. So, a few days before the gig they sat around in John's basement trying to come up with an appropriate moniker. They weren't having much luck when John's older brother Bill piped up, 'Why don't you call the band Rush?,' and Rush it was."

After honing their chops for a few years on the local bar circuit (and shifting their line-up a few more times), the band recorded their debut single, a 1973 cover of Buddy Holly's "Not Fade Away."

It was a formidable blueprint of a sound they'd later refine with more clarity. Alex Lifeson rips out a Jimmy Page-styled guitar solo, with Geddy Lee anchoring the distorted boogie with an expressive bass line. Then there's John Rutsey's contribution, a straight-ahead drum chug with an occasional snare roll blast. The b-side "You Can't Fight It," co-written by Lee and Rutsey, offered the drummer more room to stretch out. His punishing triplet fills are the track's clear highlight.

Listen to Rush Perform 'Not Fade Away'

Later that year, the band set to work on their self-titled debut LP, a Led Zeppelin-inspired hard rock set co-authored entirely by Lee and Lifeson. Legend has it that Rutsey was supposed to write the lyrics, but he withdrew, leaving Lee to pick up the slack. Given the dire music scene in Canada, the trio set their sights on breaking through in the United States – and they eventually did, thanks to an initial blast of support from Cleveland radio station WMMS, who added lead single "Working Man" to their regular rotation and soon found themselves pelted with calls asking when the next Led Zep album was coming out.

"Part of the general attitude in Canada is, unfortunately, the people coming out to see you, not all of them but quite a few of them, go, 'Oh, well, they're a local band. How good could they be?'" Rutsey noted in the 2010 documentary Beyond the Lighted Stage. "It's funny, you know, when other people from the States come out and see these local bands, they go, 'Man, these guys are fantastic!'"

With its crisp, hard-hitting riffs and relatable lyrics about the 9-to-5 lifestyle, "Working Man" became a hit in Cleveland, propelling Rush to a record deal (and LP re-release) with American label Mercury, along with series of high-profile opening gig slots for bands like Uriah Heep and Kiss. But Rutsey wouldn't be a part of that breakthrough success. His last gig with the band came on July 25, 1974, at the Centennial Hall in London, Ontario.

Since then, fans and rock historians – and even Rush associates – have cited various reasons for Rutsey's departure, including concerns related to his diabetes condition to general band dysfunction. But Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson have remained fairly consistent with their story.

"He was a diabetic, but he was handling that fine," Lee told Matt Pinfield in a 2003 interview. "That, I don't think, was the reason he left the band. It was kind of a combination of things. I don't think the life of a touring band really appealed to him in some ways. He kind of shied away from that, and I don't think he could make that commitment that was going to be required in order to do a big American tour."

Later in the same chat, Pinfield noted the sudden shift from blues-rock to prog offered on 1975's Fly by Night. And Lee emphasizes that this very metamorphosis had also put a strain on the trio.

"Well, Alex and I had been going in that direction, and that was another area of concern that we had about John Rutsey being in the band," Lee continued. "We were writing things like, for example, the whole intro to the song 'Anthem' on Fly by Night. That was written by Alex long ago, when John was still in the band. I remember jamming it with John, and he wasn't really into playing like that because that required a real active drummer, and he was a real 'lay down the backbeat' kinda drummer."

Listen to Rush Perform 'Working Man'

Meanwhile, former manager Vic Wilson maintained in Beyond the Lighted Stage that "it wasn't for his ability to drum that he was let go. It was for health reasons."

Alex Lifeson, in the same film, said Rush "went from getting this offer to getting an advance to buying equipment. Everything was happening very, very quickly. I don't think that John really felt comfortable with what was happening. We talked about musical differences, and he was a much more straight-ahead rock kinda guy. He was more into Bad Company, whereas Ged and I were more into Yes and Genesis and Pink Floyd and bands like that. If we'd stayed on the Toronto local circuit, we probably would have stayed together, and that would have been fine."

The late Rutsey mostly avoided the media in the following years, so little is known about his history after exiting the group. Various undocumented sources point to a Lifeson radio interview with Rockline in 1989, during which the guitarist says he'd managed to stay in contact with his old friend, who at that point had gone into bodybuilding.

After years of fan protests, Rush were finally inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2013. Though they clearly had a sense of humor about the long-overdue recognition, the band appeared grateful – in that trademark Canadian way – for the honor, thanking their families and fans.

Only Rutsey, whose 2008 death was blamed on complications from diabetes, wasn't inducted with Rush. Some fans were outraged over the snub. Then Lee, Lifeson and Peart failed to mention Rutsey in their acceptance speeches.

Still, to claim Rush haven't honored their former bandmate would be short-sighted: In addition to telling his story on Beyond the Lighted Stage, the trio recognized their first chapter by including performance footage with Rutsey on the Time Machine 2011: Live in Cleveland DVD.

"Our memories of the early years of Rush when John was in the band are very fond to us," the band wrote in a statement following Rutsey's death. "Those years spent in our teens dreaming of one day doing what we continue to do decades later are special. Although our paths diverged many years ago, we smile today, thinking back on those exciting times and remembering John's wonderful sense of humor and impeccable timing. He will be deeply missed by all he touched."

Rush Albums Ranked

You Think You Know Rush?

More From Talk Radio 960 AM